A History of Pysanka

Symbolism

A History of Pysanka

Symbolism

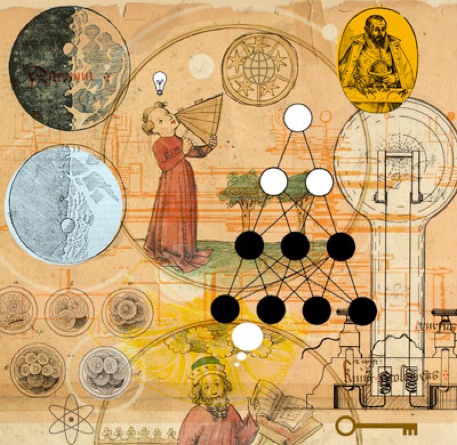

A great variety of decorative motifs are found on pysanky. Because of the egg’s fragility, no ancient examples of pysanky have survived. However, similar ornamental patterns occur in pottery, weaving, wood carving, embroidery and other traditional crafts, examples of which have survived through the ages.

The symbols which decorate pysanky underwent a process of adaptation over time. In pre-Christian times these symbols imbued an egg with magical powers to ward off evil spirits, guarantee a good harvest, insure fertility, and bring a person good luck. Pysanky were talismans, ritual objects.

After 988, when Christianity became the official state religion of Ukraine, pysankarstvo and other pagan practices were banned. This banning of old religious traditions was more successful among the ruling classes. The practice of creating small ceramic pysanky, which were included in the graves of upper class women and children, disappeared entirely.

And different regions re-interpreted the old symbols in different ways. Some saw the old eight-pointed sun symbol as a flower (ruzha), others saw it as just another star. There berehynia was probably the most variably re-interpreted, although the serpent became a snake, a spiral, a snail, an “S,” or even a shepherd’s crook (yurok). A trident/lotus motif became a bear or cat paw, a chicken, duck, magpie or goose foot, or a three-leafed plant (clover, “trylyst”).

Additional changes occurred in more modern times. In the diaspora, the pysanka transitioned from a talismanic object to an art object, and its old meanings were confused or forgotten. To fill this knowledge gap, modern diasporan authors often created new names for the symbols (e.g. Onyshchuk) as well as creating new motifs (wheat, poppies). The symbols were given new meanings. Long lists were produced, with each different motif being assigned a (sometimes) new, specific meaning. No longer were pysanky considered as a whole, but broken down into their constituent elements. As the old designs were forgotten, new ones were created, a mix of old and new, and of the various Ukrainian regions and the new land. Mariya Lesiv, in Canada, has documented this process.

As pysankarstvo diffused out of the Ukrainian community and became adopted by crafters of all ethnicities, more information was lost, and more new meanings created. Many of them seemed more “New Age” than traditional folk meanings. And these new writers of pysanky treated them as small rebuses into which they could encode their own messages.

In Ukraine, there was a huge loss of knowledge in Soviet times, when pysankarstvo was banned by the Russian regime as a religious practice. Very little was written on the subject until recent times. In 1969 Binyashevsky published his small tome, where he rediscovered (and often renamed) old designs; in 1972, Markovych wrote about Lemko pysanky, including “Soviet” designs as a nod to the new regime. Much folk memory was lost.

Since Independence in 1991, there has been a resurgence of interest in the pysanka and pysankarstvo, and new, more scholarly books have been written on the subject. Selivachov has written extensively on motifs in Ukrainian folk art, and other authors have included essays on pysanka symbolism in their books (most notably Manko). In the course of their research, scholars have unearthed the ancient, pagan meanings of pysanky which had been, for the most part, long forgotten.

In this section, and on this site, I will try to hew to the more traditional Ukrainian interpretations of the meaning of the folk motifs found on pysanky, except where noted.

Back to MAIN Symbolism home page.

Back to MAIN Pysanka home page.

Back to Pysanka Index.

Search my site with Google

Pysanka symbols through the ages